My tía and tío have a home in Aguadilla. I’ve often dreamt about it since my childhood. Stalks of flora taller than me are nestled beside their garage door. I note that they look like feathers jutting from the soil, and that the house itself, with a roof that’s creamy and slightly off-white, reminds me of my skin when it’s kissed by the sun: a vivid, peachy ochre. Speaking of feathers; there’s a lantern housing a bird’s nest. I notice a few roosters outside in the yards nearby, squawking while they kill pests; I hear they make great pets.

Slim palm trees stretch outward like fingers, but those, as spectacular as they are, aren’t what I’m interested in seeing. My tío has a banana tree that he harvests annually, and a special place packed with mysteries and natural wonders my tío chose to cultivate and preserve. At least, that’s what I’ve conjured whenever thinking about it. I’ve only seen it through photos; one with my nephew beaming with his straw jíbaro hat on as he prepared to discover the secrets locked within it for himself.

I remember dreaming about finally visiting them, seeing the majesty of El Yunque, hearing the melodic songs of the coquí that are almost indistinguishable from birds, seeing the shores of Puerto Mosquito glow brighter than neon lights while an ocean of stars shimmers above it every night in reciprocation. I feel my skin tingle as the tides tickle my feet, the first time I’ve ever touched water in years since the onset of my Epilepsy. I have no fear of drowning from a seizure as I swim through the currents, for I’m one with them; I become a mermaid, a child of Yemaya Herself, returning to my home.

I remember dreaming about the air’s stickiness, a mist that permeates it in the rainforests like a curtain, and waterfalls pouring through walls of moss-covered stone that towers above me in the shape of a cul-de-sac; foliage peppers its mountains and I imagine it’s an Impressionist painting. Then, I notice something moving in the trees, but it’s just a small gang of parrots with feathers evergreen like the canopy they’re perched within. My eyes never grow tired of seeing them.

I remember dreaming about visiting Cabo Rojo and Las Salinas with my cousins; giant dunes of salt are taller than any buildings dotted around them. There are lagoons there with rosy, crystalline water that reflects the clouds hovering above; the sky bleeds into its surface. I hear thousands of birds travel here, feasting upon shrimp in its mangrove swamps, and make it a point to observe them for myself. Fuck the gentrified tourist resorts; these natural wonders are the true marvels.

I remember dreaming about Loíza; there’s a building there painted in the likeness of the Puerto Rican flag, and countless others in barrios with murals on them. A sea of Black faces in myriad shades abounds here. Vejigantes in brilliant, dynamic costumes with intimidating trickster masks are present at a festival taking place. If my health ever improves and my Meniere’s diminishes, I’ve often thought about trying to become one. As an Afrolatin@, this place is especially important to me, because it, like many places in Puerto Rico, proclaims that our nation is just as Black as it is “Brown”.

I remember dreaming of Museo El Cemi in Jayuya, rife with histories and narratives preserved within a building carved like the idols of its namesake; Taíno hieroglyphs chiseled into la piedra escrita; portraits hewn in stone that remind me of the people whose presence is indelible in this space. It’s even named after a Cacique, like many of our nation’s places were: Hayuya. They, however, are not the only ones whose presence is felt in this municipality; a bombing occurred here. A revolution that could’ve been is woven into every street corner. Yet, there are some, it seems, who’ve forgotten it.

I remember dreaming of San Cristobal in Old San Juan, a fort centuries old that overlooks the sea. An old, ivory church is also found here, although I’d never visit beyond the sentimental. Instead, I find myself traveling past colonial walls and obscured pathways into La Perla while I sip juice from a coconut. This place has history as well; freedmen and other non-whites were once forced to live here, segregated from the rest of the city, and that legacy shows. It took a music video beloved internationally for people to actually care about it, and even then their interest is questionable. But that’s another story.

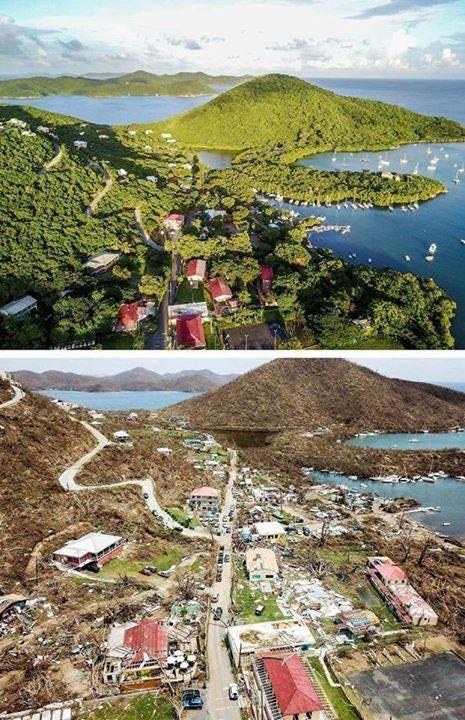

I remember my prima showing us an aerial photo of La Parguera in Lajas, covered in greenery that buried the town adjacent it. Then, I remember Maria, that wraith of a hurricane that stripped the region bare. All I saw were demolished trees amongst the soil and a town pummeled by it; nothing was spared.

I remember hearing that Aguadilla was “destruida”; wondering if my relatives in Caguas and other places were okay, many of which were flooded; homes without roofs being subjected to seemingly endless rain; ICUs failing in hospitals, many of which, like the rest of the island, lost power; nights without the Coquí to comfort us with their songs. The military and FEMA neglecting our people, despite claims otherwise; mothers without milk to feed their children; disaster Capitalism rearing its head.

Of course, there was also the legion of outraged articles written by people that claimed to care about Puerto Ricans, but did not care for our brethren in the rest of the Carib. They were amazed by diet-Underwood’s indifference, but we’d long known him to be despicable. They claimed to care about the Jones Act, but did not care about the people holding our infrastructure hostage. But these are their stories, not ours. This was not my dream.

My tía and tío have a home in Aguadilla. I’ve often dreamt about it since my childhood. In my dream it has finally been restored — we’ve even planted new banana trees — although it is forever changed. All of the island is. We reported, reimagined, and revived our community. We refused to allow our oppressors to tell our narratives for us. We survived, like we always do.

I walk beaches barefooted for the first time in many years, cherishing every grain of sand that sticks to them. They will not be privatized; they will always be free. I admire the sound of the coquí in the forests at night, the timeless music and voice of the Eggún heard in Ifa drumming sessions; the looks of approval my relatives give when eating my handmade pasteles and arroz con gandules — not to forget the recaíto I made just for them. I may or may not be enjoying my prima’s coquito.

The Union’s military will never have a presence here again, and any aid they offer will be at our discretion. A board of robber barons we did not elect will no longer close down our schools or slash healthcare and the minimum wage for the employed; the police will not operate like a mob in low-income, predominantly Black communities, more will accept those like me who are LGBT, and the politicians obsessed with assimilating to further their destructive Capitalist interests will no longer have a chokehold in the political conversation.

I remember dreaming that this place will not be a colony, a “Commonwealth”, nor a state. It will not even be Puerto Rico. It will be the nation it was meant to be, with a name its people once gave it. It will be the Land of the Noble and Valiant. It will be Borikén.